Do we spend too much on health care?

According to my post yesterday, it may seem like the answer is ‘yes’. The US spends by far the most money per person and the largest share of its economy on health care. While cross-country comparisons often grab the headlines, a New England Journal of Medicine Perspective by Katharine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra argues that the results of those analyses should be viewed with caution for at least 3 reasons.

- Income differences. Health care is a luxury good. When I say “luxury good”, I do not mean to say that it is only for the rich, but rather luxury as defined economics. That is as income increases, the share of income that goes to health care typically increases. Baicker and Chandra write that “The fact that U.S. incomes are nearly 25% higher than U.K. incomes, for example, suggests that we would be spending 15 to 25% more on health care.”

- Quantity often is not measured well. One could compare cost per office visit or diagnostic test. In this US, however, there is much more specialist care and high-technology diagnostics. Thus, an “office visit” for a general practitioner is not comparable to an “office visit” with a cardiothorasic surgeon even both events may be classified as “office visits” in the data.

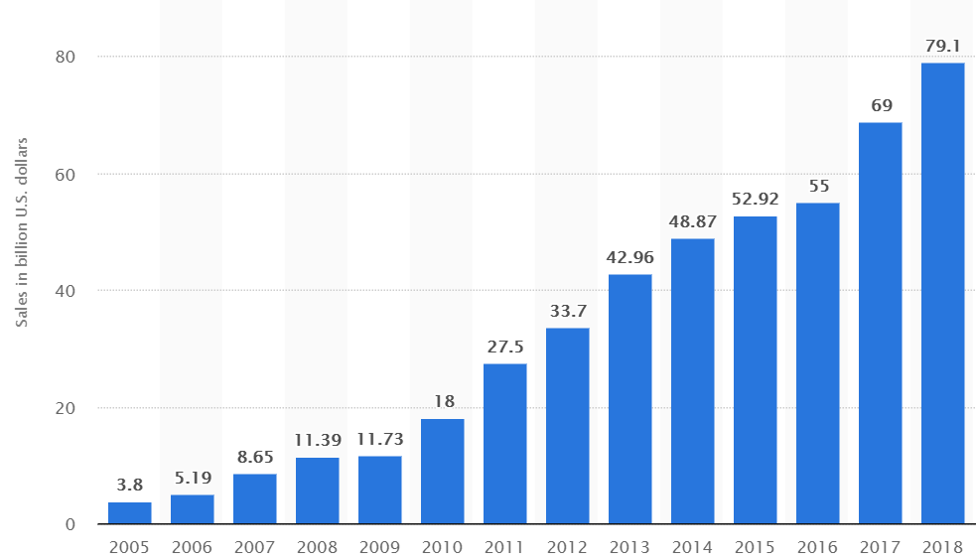

- Quantity, quality and cost are inter-related. Consider the graph below. Look at this a large increase in cost. Is this a problem? Perhaps not. This is a chart of US smartphone sales over the past 2 decades. No one complains about these costs since it’s clear that the quality has gone up tremendously, and consumers value smart phones more than the rise in cost. Nevertheless, in health care increased costs are often seen as a universally bad thing. Baicker and Chandra take a more balanced approach. They write: “Knowing whether prices are ‘too high’ hinges on understanding the forces that determine these prices and on whether lower prices would result in desirable or undesirable changes in the care delivered. For example, high prices that result from anticompetitive mergers suggest different policy reactions than high prices that result from patients choosing more expensive providers over less expensive ones: for patients, 10% higher perceived quality might be worth paying 30% more. If prices truly reflect patient demand for valued care, then administratively setting lower prices may harm patients.”

So what is the solution? The authors recommend focusing on value. I wholeheartedly agree. Policymakers and payers should measure whether new drugs, surgeries and health care improve outcomes significantly relative to the cost; health policies should not be evaluated based on whether then increase or decrease health care spending, but whether the increase or decrease the value society receives. A focus on “value” truly is the key.

from Healthcare Economist https://ift.tt/31KxQ1P

No comments